Monument + Database

The Monument pillar of Japanese Canadian Legacies is comprised of two components: the monument itself, and a database of names, which will be configured onto a monument wall.

Japanese Canadian Legacy Monument

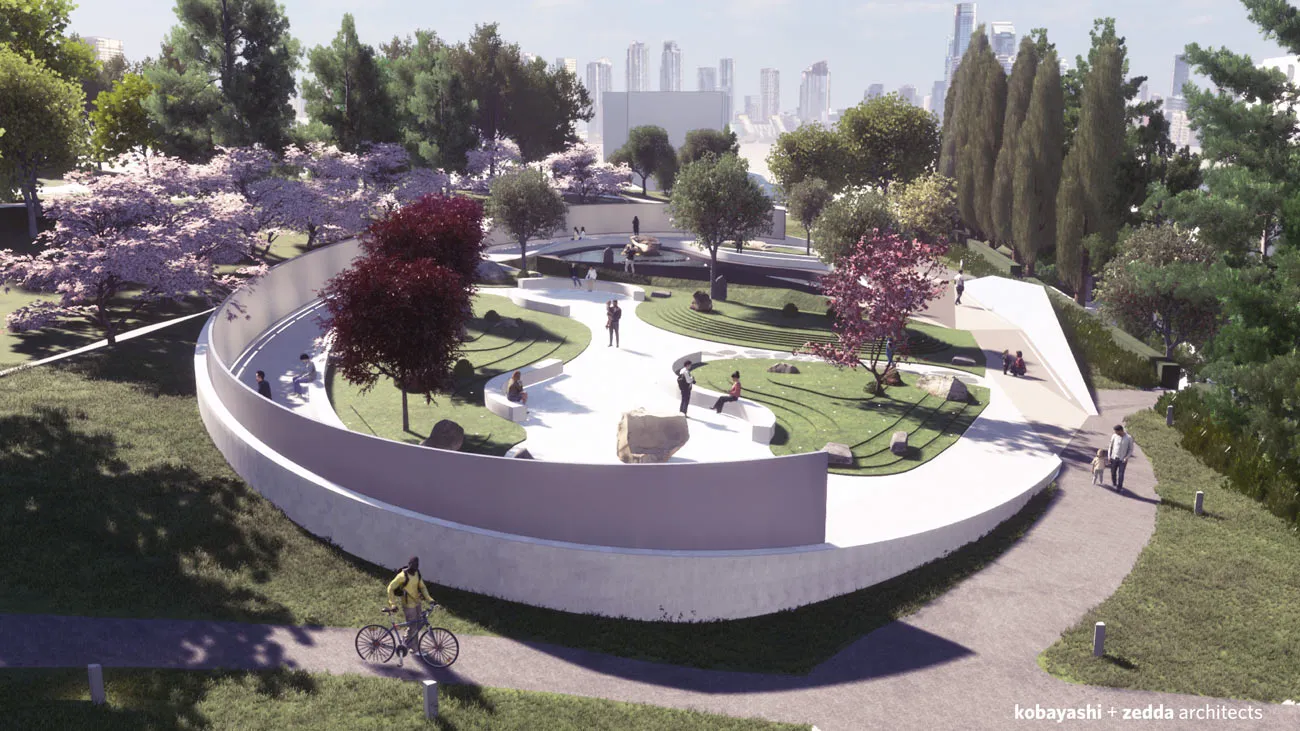

As a lasting legacy, a monument will be built close to the parliament buildings in the provincial capital of Victoria. A place of pilgrimage, reflection, remembrance and learning, the monument wall will frame the story of the uprooting, incarceration, internment, dispossession, and permanent displacement of the nearly 22,000 Japanese Canadians who lived in the coastal areas of BC. This project will be led by the BC Government jointly with the Japanese Canadian Legacies Society. Early work is underway with the team at the BC Government to cost the project, which will be open for a competitive bid.

– Susanne Tabata“The dream and vision for the monument is that it will envelope the origin story of Japanese Canadians who settled in cities, towns, and villages, primarily along the coast. The tactile names on the wall help to recognize individuals and families and where they lived before the forced uprooting, seizure and forced sale of assets, incarceration, internment, permanent dispossession, and two waves of displacement. We hope there will be a digital version of this project wherein people can search for the names and where they are situated on the monument. Japanese Canadians have produced many talented architects, designers, and artisans including Japanese landscape gardeners. There has been a three year build up of pro bono input which has had a big impact on moving the monument forward. A big thank you to architectural writer John Ota for input about the concept; Rob Poncelot and Luke Straith of Stewart’s Monumental Works for early conversations about granite, scope and scale of size of wall; and to Kobayashi/Zedda Architects for the visual study and preliminary costing report needed to move the project forward. And to Raymond Moriyama for inspiring generations of Japanese Canadian architects. We look forward to the work ahead, and to the work being led by Michael Abe on the creation of the database of names.”

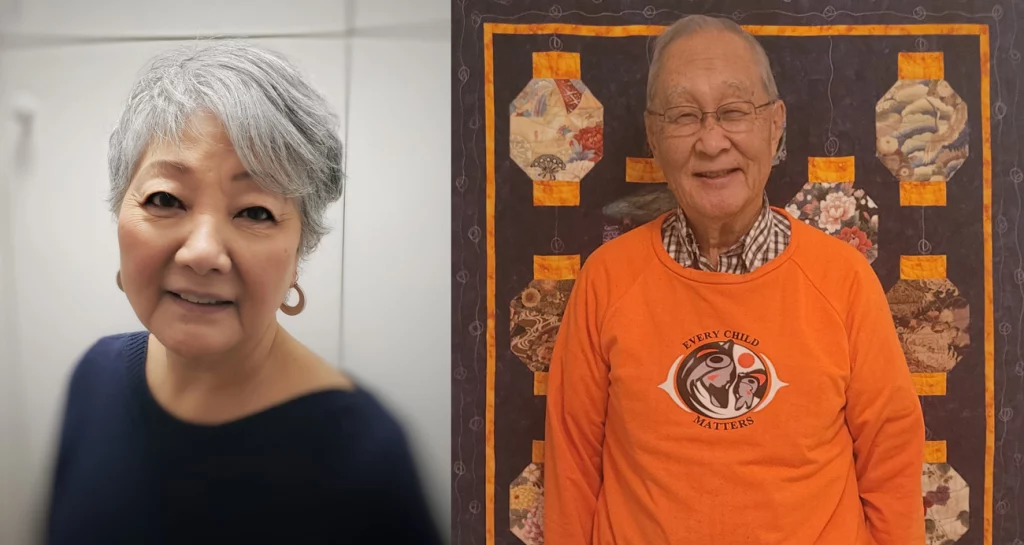

Japanese Canadian architect Raymond Moriyama, known for designing the Canadian War Museum, was one of a group of Toronto community members who mortgaged their homes to purchase land for the first Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, which he designed. Left: Raymond Moriyama. Right: Susanne Tabata. Photo: MK Abe

Japanese Canadian Legacy Monument Database Project

It has long been a goal that the monument wall will contain the engraved names of the nearly 22,000 Japanese Canadians who lived during this time in BC’s history. A separate research project is to develop a database of the names. This work will take place at the University of Victoria, and will require up to one year to complete.

Announcement

The Japanese Canadian Legacies Society (JCLS) is pleased to announce the appointment of Michael Abe as Project Director for the JC Legacy Monument Database Project. Mike will be liaising directly with the JCLS project office to produce this work, leading his own research team under the Humanities Department at UVIC. The goal is to produce a master database of names to be installed on the monument in Victoria. Mike has assembled an advisory team that includes Edmonton’s David Mitsui along with Linda Kawamoto Reid and Lisa Uyeda, both from Vancouver, and Kaz Shikaze and Jan Nobuto from Toronto.

A sansei (third generation Japanese Canadian) Michael holds a BSc in biology from McMaster University in Hamilton, where he was born. He grew up playing hockey and other sports in Burlington, where the family moved soon after he was born. After university he spent a number of years in Japan, studying sumie, shuji, and martial arts. While in Japan he met his wife and they relocated to Victoria in 1993 with their young son. They have lived in Victoria ever since and both their son and daughter graduated from UViC, where Mike has worked for the past seven years as project manager for Landscapes of Injustice (LoI) and is currently on leave from his role as project manager on a new project, Past Wrongs, Future Choices.

Interview: Michael Abe

You have a long-time interest in history in Japanese Canadian history, and the local communities, in particular. When did you first discover this passion?

I was fortunate to see the formation of a Japanese Canadian cultural centre in Hamilton around the time of the JC Centennial. The centre was a busy hub for our community, bringing together several generations of families from the area. Not only were many long-time friendships formed, but it was also a place for the Japanese heritage and culture to be honoured, preserved, and shared with the local community.

I later became involved in the Victoria Nikkei Cultural Society in Victoria as well as the Victoria Japanese Heritage Language School Society which my children attended. When the earthquake and tsunami disaster struck Japan in 2011, I was involved in bringing the local Nikkei groups and community together quickly to organize a number of fundraising events and initiatives.

What’s your own family history as is relates to the wartime years?

On my mother’s side, great-grandfather Takejiro Toyota arrived in 1907 from Fukuoka-ken, followed three years later by his wife, Hama and my then 13-year-old grandfather Shoshichi. Later his brother Daigoro also arrived, and they married a set of Obuchi sisters, Hanayo and Kiriye. They settled on Vancouver Island and worked in Paldi (Mayo), a sawmill community near Duncan, BC. They would be uprooted to Popoff, New Denver and Slocan. Takejiro rests in Slocan Cemetery where he died in December 1942.

On my father’s side, Grandpa Isamu Abe came from Beppu in Oita-ken, as did my grandma, Yachiyo. They settled in Port Alberni. Grandpa was sent to Angler and would be reunited with the family in Lemon Creek.

Both the Abe and Toyota families would move to the Hamilton and Kitchener areas after the war ended.

Were you brought up knowing the wartime history, or did you learn about it later, like so many of your generation?

I grew up in a very suburban, WASP community in Burlington, completely assimilated, so much so that I didn’t realize I was a visible minority until my teenage years.

As mentioned earlier, it was great to have the cultural centre as a place to help learn more about my heritage.

I first learned about the internment in Grade 8 when we had to interview a family member about our family history, and it was difficult to convince my father to be interviewed. He finally relented and I remember it being a real shock to hear about the internment. He remained tight-lipped about it for much of his life. One of my motivations to learn Japanese and go to Japan after university was to be able to talk to my grandma to learn more about her experiences.

Fast forward to 2012, when we unveiled a commemorative bench in Lemon Creek. My dad openly spoke about his past when asked by those present. That was the pinnacle for him, the ‘people are interested in hearing my story’ moment. Unfortunately, he would pass away less than two months later.

This is a huge project, gathering all these names, what prompted you to take it on?

I was involved in the Landscapes of Injustice which was a total of eight years. The first four years consisted of research about the dispossession of Japanese Canadian property and the second phase was the development of knowledge mobilization initiatives that included a travelling museum exhibit, publications, and teacher resources. It also resulted in a database of all the research we acquired over the course of the project. We were fortunate to partner with the Library and Archives Canada to enable the case files to be digitized and metadata added to allow them to be easily searchable. In the past number of years, I have seen first-hand the incredible impact that these files have had on researchers and community members as they learn more about their family history. From the positive feedback and gratitude from the community, I feel it is the most valuable and important output of the project, the files and what they contain, filling in the blanks of the silence.

I can see how the infrastructure of this database will be of great assistance to the Monument Database Project. It will give us a very good start, but it will be a large undertaking that we are embarking on to ensure that the list is as complete and accurate as possible.

For some, it’s been a long-time dream to pull together a complete list of those impacted by the government wartime policies. How will you go about collecting the names and determining who will be on the monument? Which is how many, by the way?

Because this is part of a BC Redress package, the focus on this monument is to recognize and honour those Japanese Canadians who were forcibly removed from coastal British Columbia due to the policies of exclusion by the Canadian Government in 1942. I am privileged to have access to the expertise and sound advice from members of my advisory board, David Mitsui, Linda Kawamoto Reid, and Lisa Uyeda. By the time you are reading this, we will have rounded out our advisory board. This board will play a key role with input into the criteria of who will appear on the monument. Although the criteria have not all been finalized yet, the defining question for a person to be on the monument will be “Where were you in ’42?” as plans are to categorize names by where they were living in coastal BC at the time that they were forcibly removed outside the 100 mile “protected” zone. It will take cross referencing list from various sources over the course of a year to be confident we have the correct spelling of all 21,462 (?) names.

An important part of this process will be extensive community consultation sessions, calling on these people and their descendants to help confirm their family names.

You’re a sansei, a generation removed from the internment years and brought up very much within the Canadian mainstream, but you have immersed yourself in traditional Japanese arts like aikiko and sumie and have brought up your own kids to value their cultural heritage. What has your heritage and your exploration of it given to you, do you think?

Although I am very Canadian, there are aspects of Japanese traditions and culture that I enjoy through the practice of these arts. While it is great to see artists in North America freely innovate to adapt to North American predilections, I prefer to stay as traditional as possible, continually returning to basics and first principles. I could speak more but I’ll leave it there.

As a Japanese Canadian, what does the monument mean to you and what do you hope the monument will offer to those who experience it, both other Japanese Canadians, and the general public?

I can envision the monument becoming a destination, with several generations of Japanese Canadian families travelling to see and touch their own names and those of their ancestors and to pay their respects to the communities that once existed throughout BC. It will be a place of healing, and learning. For those not connected to this history, I hope that they will learn more about this dark chapter in Canadian history. I feel very privileged and honoured to be given the opportunity to contribute to this important initiative.

Is there a way for interested people to get involved in this project?

The Monument Database project has budgeted resources for hiring researchers to help collect and analyse data from various archives. Throughout the year we will post positions on our website, https://jclegacies.com/six-pillars/monument/ for members of our community to join our research team.

Enquiries can be sent directly to me at mkabe@jclegacies.com

Jack Kobayashi

Jack Kobayashi recently lent his pro bono design skills to the Japanese Canadian Legacies Society to build out a preliminary costing report for the Monument.

“As you travel away from the historic settlements of Canada, space opens up, at first by prairie and then mountains and then by cold, snow and ice. The architecture of the maritimes and Central Canada is constrained by historical and contextual built landscapes. The west and north opens up and allows for more object buildings in the landscape. That equates with design freedom and opportunity.” – Jack Kobayashi

Jack Kobayashi: opening up space for the “third place”

Like the vast majority of prewar Japanese Canadians, Jack Kobayashi’s family started out on the west coast before being uprooted and dispossessed, eventually moving east of the Rockies in line with government directives. Jack was born in Montreal, Quebec in 1963, where his father worked for Eagle Toys, designing a version of table-top hockey that was popular across Canada. Jack grew up playing with various prototypes of the game, a unique opportunity for a youngster.

After high school, Jack studied urban planning at the University of Waterloo under Kiyoshi Izumi, a notable architect with Izumi Arnott Sugiyama in Regina, Saskatchewan. He then studied architecture at the University of Manitoba, where his uncle, Ron Kobayashi, also studied architecture. Jack received a Bachelor of Environmental Studies from the University of Waterloo in 1986, and a Masters of Architecture from the University of Manitoba in 1992.

After graduating, Jack worked for several firms before moving to Whitehorse, Yukon in 1991 and co-founding a new architectural practice with BC-registered architect Florian Maurer. This firm would become the predecessor firm of Kobayashi + Zedda Architects Ltd. (KZA), formed in 2002 with Antonio Zedda. KZA is the largest architecture firm in Canada’s north and has been involved in the transformation of downtown Whitehorse into a vibrant living and working community. Since its inception, the firm has worked on more than 1,000 design projects in the Yukon, Northwest Territories, Alberta, and British Columbia, varying in scale from private residential renovations to the $65 million Whitehorse Correctional Centre. The firm’s partners have a combined experience of nearly 60 years working in the Yukon in every eco-region of the Territory. The firm received the 2006 Professional Prix de Rome from the Canada Council and in recent years has become recognized throughout Canada for its First Nations and sustainable architecture.

Interview: Jack Kobayashi

Let’s start with your family’s trajectory in Canada. Where did they live before the war, where did they live during the war, and how did you come to be born in Montreal?

Jack’s mother was born in Kitsilano, on the second floor of her family’s dry cleaning business, Reliable Cleaners, near the corner of 4th and Vine Streets. The business was seized and sold during the internment and continued to operate under the same name, at that location well into the 90s.

Jack’s mother, a ten year old girl at the time of internment, was sent with her family to the camp at Tashme near Hope. BC. Her father, not yet a Canadian citizen, was separated from the family, sent to work on a road camp and his whereabouts was unknown until he was reunited with the family at Tashme many months later.

Jack’s father was 15 years old in 1941. His father’s family was permitted to leave the restricted area near the coast to tend to family business interests in Blind Bay in the BC interior. The family business failed before the war ended. Jack’s father struggled through several menial jobs in Kamloops before realizing that the only way to thrive was to move east, as did many Japanese Canadians.

At one point, the City of Toronto began to close its doors to the influx of Japanese Canadians from the west and many families moved further east to Montreal, where the political reception was much warmer.

As a boy you wanted to become a police officer but ended up drawn to architecture. How did that come about?

I was fascinated with police cars and uniforms. I created several volumes of hand drawn books called the ‘Book of Cops’. These still survive today. A while ago I was flipping through one of the illustrated volumes when I noticed that I had drafted a ground floor layout of a police station. The was likely the critical turning point in my future career.

Is there anything about your family’s wartime experience that impacted your approach to your studies or your work?

I tend to favour the underdog. We don’t do a lot of exclusive, private residential work. We tend to favour the projects that help groups of people, disadvantaged by circumstances beyond their control, community housing, emergency shelters, correctional centres etc…

You studied urban planning before shifting to architecture – how did those initial studies impact how you approached architecture?

More often, people will start their academic careers in architecture and broaden their scope into planning. I did the opposite. The planning component provided a very good baseline for all things architecture.

Your time at the University of Manitoba had a big influence on you. Can you talk about that?

It was my first time living in a smaller city, a prairie city, outside Central Canada. It was fascinating to see Ontario and Quebec through another lens and gave me some impetus to venture further afield from my childhood roots.

In researching this interview, you have worked with, or been influenced by, a number of Japanese Canadian architects, including Raymond Moriyama. Is there something about the approach of these architects that resonates with you in a particular way?

Moriyama’s architecture has a zen-like quality to it. It is very Japanese. His massive Ontario Science Centre could barely be noticed from the street. The majority of the building was hidden as it cascaded down a ravine. It’s a building without ego.

Moriyama’s Toronto Reference Library is one of the great interior spaces in this country. Like the Eaton Centre but catering to silence. Acoustically, the space offers a dull roar of calming white noise.

I visited these buildings as a child often and they have left an impact on me to this day.

Your studies and work have taken you from Waterloo, to Manitoba, and now Whitehorse, far from the urban centres where most people in your field are drawn to. Is there something about more remote areas that call to you in some way?

As you travel away from the historic settlements of Canada, space opens up, at first by prairie and then mountains and then by cold, snow and ice. The architecture of the maritimes and Central Canada is constrained by historical and contextual built landscapes. The west and north opens up and allows for more object buildings in the landscape. That equates with design freedom and opportunity.

Why did you choose the far north as a home base?

Upon graduating from architecture, all of the opportunity lay in Vancouver. Many of my class members moved there for the work. I wanted to move to a place that nobody desired.

In addition to running your firm, you and Antonio Zedda own and operate a bakery in Whitehorse. The two of you also own Horwood’s Mall, where your own offices are situated. This seems rather unusual for an architecture firm. Can you tell us more about that?

In his book, ‘The Great Good Place’, sociologist Ray Oldenburg revealed that it was critical for every person to have a ‘Third Place’ – the first and second being home and work respectively. At the time, downtown Whitehorse did not have a very good ‘Third Place’ but we have since created one in our Baked Café + Bakery.

What was your involvement in the consultation process for the Victoria Monument project?

My first task was to review all of the valuable engagement work that had been completed by others like Susanne Tabata of the JCLS and Elizabeth Matheson from the BC Attorney General’s office. Along with site specific data including geotechnical, topographic, horticultural and site services data, I was able to direct a team of designers to develop a concise physical vision of the Memorial project based on the early data.

It should be noted that there will be additional engagement with First Nations Rightsholders subsequent to the Visioning Report.

Is there any advice you have for someone interested in architecture as a calling?

This would need to be an entire chapter on its own. Do what inspires you.