In Celebration of Women

The first Japanese immigrants began arriving in British Columbia in the 1870s, young men looking to earn their fortune before returning to Japan. Before long, some began to see Canada as a new home, a place to settle and raise families. The first recorded issei woman to settle in Canada was Yo Shishido, who arrived in 1887. She and her husband, Washiji Oya, ran a store on Powell Street. Their son, Katsuji, the first nisei, was born in 1889. With the arrival of women, Japanese Canadian communities began to form on Powell Street, in Steveston, in the Fraser Valley, in Victoria, and in smaller communities up and down the coast, wherever there was work.

Due to laws that barred Japanese Canadians from most professions on the basis of race, the majority of Japanese Canadians worked in the resource industries including fishing, farming, logging, and mining. It was a hard life that required all family members to pitch in. The woman did double duty, taking care of the family’s and needs while also working long days, often doing hard manual labour.

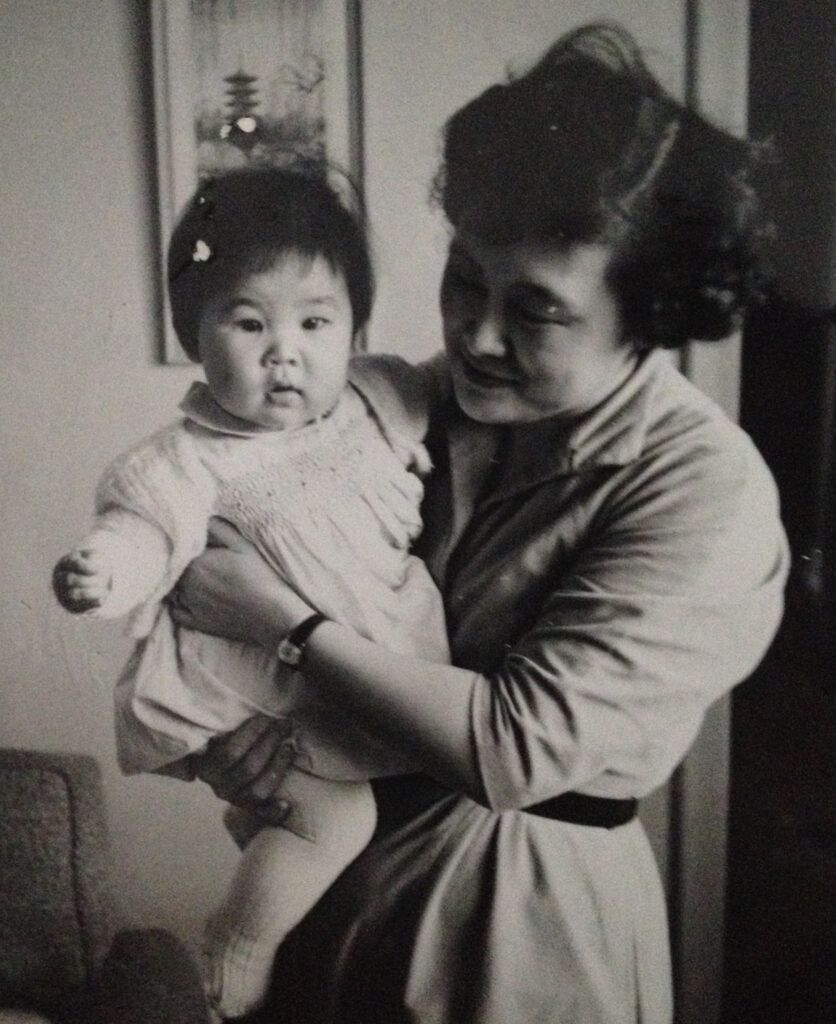

In celebration of Mother’s Day, Japanese Canadian Legacies pays tribute to the women who have done so much to create the community we have today in the face of many challenges. Patti Ayukawa is an advocate of Japanese Canadian wellness programs and sustainable systems that supports community awareness of safe, restorative JC spaces and connections.Patt’s mother Midge was rooted in the community as a scholar and mentor dedicated to accurate and community informed preservation of Japanese Canadian history. Ted Akune is a retired educator who worked in public and private school education. He worked as a teacher, counsellor and administrator and specialized in international students and programs. In retirement, Ted served on the executive board of the Steveston Buddhist Temple as President for several years and continues as Past President. We spoke to Patti and Ted about some of the women in their lives.

In Conversation with Patti Ayukawa and Ted Akune

Patti, your mother was a formidable woman. Like so many women, she juggled a career and family. What inspiration have you taken from her in terms of how you live your life?

Patti Ayukawa Thank you for saying that. My mom often spoke of the loss of having to leave her research position at the National Research Council to raise a family. What would it have been like for her if she continued being part of a team that was at the forefront of chemical research?

After she passed away, I came across an envelope addressed to her from the New Canadian with a letter from Frank Moritsugu and the clipping of an editorial called ‘In Defense of Career Women’ by an irritated Hamiltonian. She had written it when she was 17. I shared it with Karen Kobayashi who enjoyed its brilliance and used it in one of her classes at UVic. We were both in awe that mom had already become centred with her career goals and to know that she felt that it was important for a mother’s education to always surpass that of her children’s. Does that explain some of her drive to do her PhD later in life?

What about your grandmothers? Did you know them? And did have any influence on you growing up?

PA My grandmothers were like night and day. Grandma Ishii was a stoic, beautiful, wise Meiji woman. As a child I was amazed by how her hair was always perfect and her facial expression never changed. It wasn’t until we would say good bye to her at the end of one of our yearly Christmas visits that I would see her eyes show a hint of emotion. She had a quick wit. Once my sister was teasing grandma about her perfect, old lady hairdo. Her reply was, just you wait, one day your hair will be just like hers!

Grandma Ayukawa was always laughing. We would stay over at her place on Indian Road every Xmas. The best part was her frying up an entire package of bacon in the morning and being with her in the living room watching hockey or wrestling on TV.

I got to know my grandmothers not through words or language but by being with their kindness and the leaving part. I know what it feels like to say goodbye to grandmas. I wonder what it would have been like if we saw them more than just once a year. Did they feel the loss that I felt too?

When my dad died at 50, my grandma collapsed and cried all day on the couch. Layers of family grief, old, chaotic, painfully cutting. Her eldest son was gone.

I don’t have any recipes from either of my grandmothers. I would like to have at least one so I had a pattern to follow, to measure accurately, to examine a bit deeper, really understand it, observe its truth and taste what they knew. Their pathway of a precious life force that is not random.

Ted, what’s your view of women in the community?

Ted Akune My experience growing up in Steveston, if you’re a fishing family the father went out on the fishing ground for a month or two, or sometimes four of five months.

During those periods, back home the children were still fed. The mothers, the vast majority of whom worked as well, looked after the house, children, food, getting kids to school, homework, encouraging them to do as well as possible in school – and the kids did do well in school – and a lot is taken for granted. When you think about it, it’s not just our mothers, but older sisters too, and I have two. After the war, while conditions were improved, there was still that feeling because you’re Japanese – there was subtle racism, not so much in Steveston, but as soon as you left there you were often the only one and you felt it because you looked different – and that had an impact on the psyche of a person. As for women in general, not just Japanese Canadians, but if you could get an education, the only two places you could find work was a teacher or a nurse. Women also worked looking after families as housekeepers, house cleaners, etc. There were not too many opportunities for women.

In my case, my aunts, my wife, my mum, my grandmothers, my older sisters, two daughters and a granddaughter – they’re incredibly important to me and I’m grateful that they’re there to support me, even my granddaughter – she’s twenty and she still gives me a shout out – come over to Vancouver Island and visit.

In Steveston, even after the war, the Fujinkai, the women’s association, would do so much, whatever needed to be done, whether it was baking or organizing, prepping for funerals. You go to these events and you think, how did that happen? And it’s usually the Fujinkai. They’re really unsung heroes. Even to this day I marvel at their commitment. Unfortunately, they’re getting older, well into their eighties, and they can’t do everything they used to.

Patti, I interviewed your mother once many years ago, and one thing she has stayed with me ever since. She told me that the second uprooting, when the camps were closing and families were forced east of the Rockies or to Japan, was in some ways more traumatic than the initial uprooting from the camps, at least for young people of her age. Your mum would have been in her early teens when she left Lemon Creek with her family and moved to Hamilton. She said that in the camps there was a sense of safety, as they were insulated from the outside world and the racism that Japanese Canadians faced in Vancouver. She told me that during the years spent in the camps they had developed a way of speaking that blended English with Japanese. Released from Lemon Creek into the mainstream community, she was terrified of what would come out when she opened her mouth. It really struck me, talking to her, the feelings of dislocation and fear that Japanese Canadians must have felt as they endured these waves of uprootings. Did you mother ever discuss these things with you?

PA This is heartbreaking to hear that she had to go through that experience. No, she never sketched out many details of what happened. She did tell me about the depth of grief she felt when she had to say goodbye to her two closest Lemon creek friends, Peggy and Terry, whose families chose to go to Japan. Mom said that she cried so many tears that she never cried again.

It’s true. I never saw her cry.

Did she ever process that grief? The silenced emotions that followed her through her life tells that story. The family had to survive. Be strong and keep studying. Don’t be bitter. Be better.

Her parents didn’t have any relatives in Canada so it must have been a very isolating and difficult experience for them to start over in Hamilton. Maybe that is why my mother was a very independent, social person and absolutely cherished all of her friendships (she didn’t have cousins.)

Ted, did your mother talk much with you about the war years and what that was like?

TA I’m aware of the past with respect to my own family, but even within my own family it’s something we don’t talk about too much and that’s a common theme – people don’t want to talk about it. It was too emotional to talk about, what they endured, and it’s especially difficult to tell that story to their own children. They didn’t want to burden us.

We’d hear little stories and try to piece them together. My wife Rose is Caucasian, and for whatever reason, my mother was able to explain a lot to Rose. Partly because Rose was that one step removed – not direct family – mum felt it was easier to talk about what they had gone through. It’s funny – and this goes back decades – some researchers at UBC were doing a study and my mother’s name came up, and that was the first time that my mother talked about the experience, and subsequently with my wife.

And obviously Rose would share those things with me. But I never heard much about it from my mother, no.

Ted, what’s one thing you’d like to say to people this Mother’s Day?

TA I would say celebrate Mother’s Day. And if you are of Japanese descent, whether an eighth or a quarter, or a half, think beyond your mother to your grandmother, your great grandmother, your great-great grandmother, and think about what life must have been like for them back then. And if you don’t know, ask your parents, it’s important to understand your identity and your history.